EURIS update

18 Dec 2018

Leading UK Institutions provide worrying data regarding the UK economic growth post Brexit

Whilst maintaining a neutral, apolitical position on Brexit, BFPA CEO Chris Buxton reports on discussions with the CBI regarding possible economic scenarios post Brexit. Their comments were a little worrying…

In its recent discussions with Government and other leading business institutions, the BFPA, as part of EURIS has sought the views of numerous expert bodies regarding the likely impact of BREXIT on the UK economy after the UK leaves the European Union. One such body is the CBI who have engaged with the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) in conjunction with UK in Changing Europe, and Her Majesty’s Government (HMG). Their analysis is worrying.

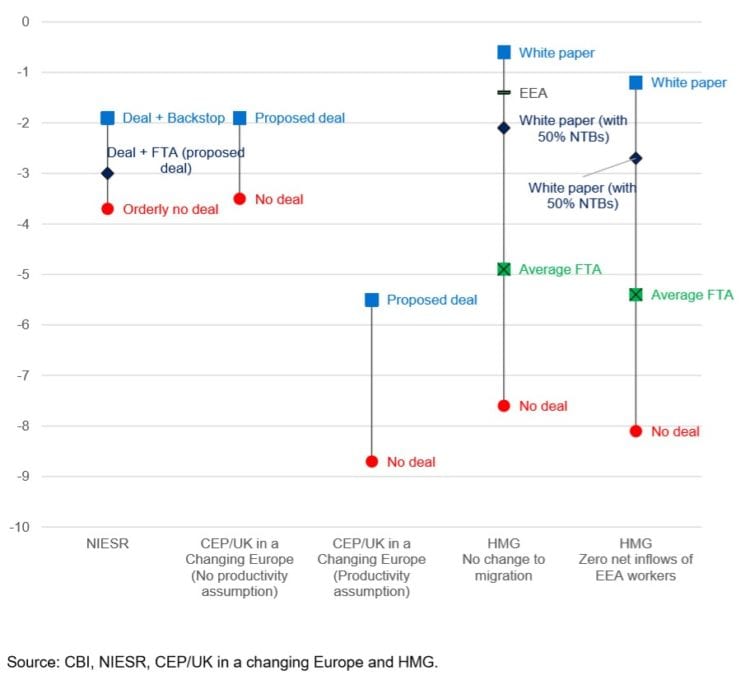

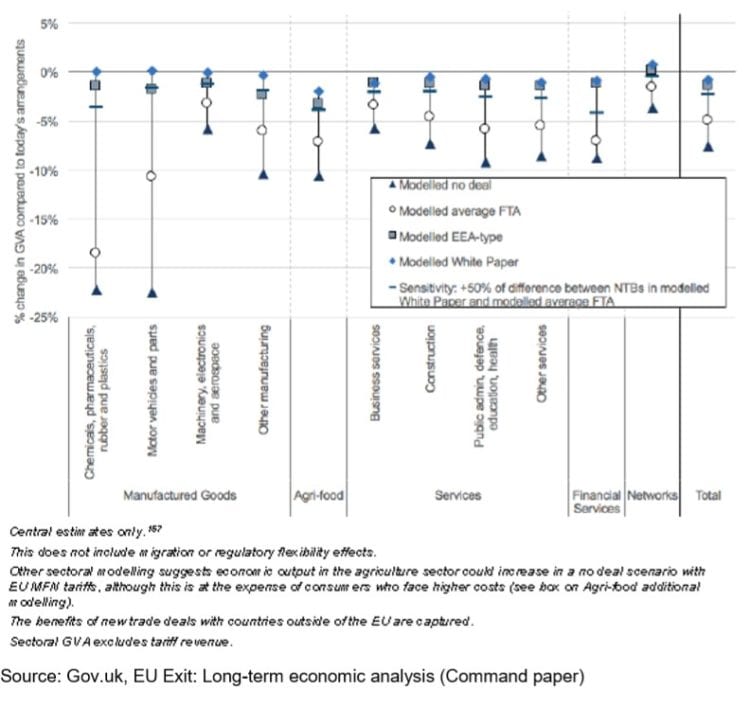

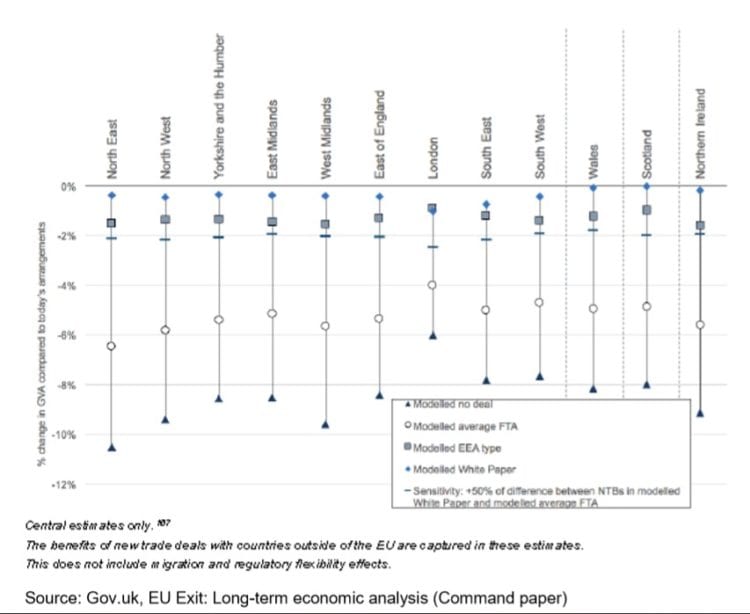

Regardless of the form that Brexit takes, all the studies find that leaving the EU would make the UK worse-off in the long term, with the risk of further short-term disruption. The impact of “no deal” is found to be particularly negative, with GDP per head expected to be 3.5%-9% below baseline in the long-run, reinforcing the importance of avoiding this outcome. All studies also model a “deal” scenario, with a number of different assumptions including tariffs, rules of origin and non-tariff barriers, particularly for services trade. The range of impacts depend crucially on whether more trade barriers lead to lower innovation and productivity growth. Sectoral and regional analysis reveals that the chemicals and motor vehicles sector would see the most negative hit in a “no deal” scenario, while the regional results showed that the North East, North West and West Midlands are the most exposed. Nevertheless, the impact of Brexit on the economy will ultimately depend on how policy and business responds.

How to interpret the analyses

In the final week of November, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) in conjunction with UK in Changing Europe, and Her Majesty’s Government (HMG) all released reports analysing the long-term impact on the economy of leaving the European Union (see Figure 2). The studies are broadly comparable in approach and seek to model the potential effects more than a decade hence—around the beginning of the 2030s. Meanwhile the Bank of England took a different tack by looking at the shorter-term economic impact of different Brexit scenarios over the next few years.

It is important to note at the outset that the analyses should not be thought of as economic forecasts for the years ahead: so much will change in the UK and global economy that it is impossible to make accurate predictions about the size of the UK economy at the start of the 2030s. Rather, what the models do is attempt to isolate the effects of specific changes, assuming all else is held constant. In particular, the modelling looks at the impact of changing trade arrangements and future migration patterns, along with other channels through which UK growth could be affected by leaving the EU. For example, as well as estimating the impact on UK-EU trade flows, the HMG study seeks to model the impact of new free trade agreements (FTAs) with countries such as the US, Australia, New Zealand, and others.

All forms of Brexit leave the UK economy worse off in the long-run…

All the studies find that all forms of Brexit leave the UK economy worse off in the long-run than it otherwise would be. Higher trade frictions—i.e. tariff or non-tariff barriers (NTBs)—between the UK and the rest of the EU impose additional costs on business that result in lower GDP (or GDP per head), relative to baseline scenarios that assume continued EU membership.

The HMG study finds that even were the UK to be successful in securing trade deals with a number of other countries, this would be insufficient to overcome the negative impact on the economy from higher trade frictions with the EU. The studies are also united in concluding that the hit to the economy could be lower under conditions approximating the government’s withdrawal agreement and political declaration, compared with a situation in which the UK leaves without a comprehensive agreement with the EU. However, the different assumptions and timeframes underpinning the various scenarios mean direct comparisons across the studies are not possible.

No surprise that “no deal” Brexit has the biggest negative impact on UK

All the studies find that leaving the EU without a deal would have the biggest negative impact on the UK economy, in both the short-term and the long-term. The hit to GDP per head ranges between 3.5% and 9% below baseline in the long-run (which is assumed to be around 2030 in the NIESR and CEP studies, and 2034 in the HMG study).

Short-term impact:

The Bank models two “no deal, no transition” scenarios where the UK reverts to WTO rules at the end of March 2019, which it labels a “disruptive” or “disorderly” Brexit. The disorderly Brexit scenario is the Bank’s worst-case scenario for the UK economy, incorporating some of the most drastic assumptions regarding future trade, disruption at the border, a rise in Bank rate, the degree of uncertainty and the level of net migration. The disruptive scenario excludes four of the most severe assumptions in order to illustrate the magnitude of their effects i.e. has lower macroeconomic uncertainty, a more accommodative monetary policy response, less disruption at the border and slightly looser financial conditions compared with the disorderly scenario. The modelling suggests that in the event of “no deal, no transition”, UK GDP could be 7%-10% lower in 2024, relative to the trend seen before the EU referendum. It is important to note that these are not the Bank’s forecasts for the economy in the event of no deal, but scenarios it used to test the resilience of the banking system under extreme, but plausible economic shocks.

Long-term impact:

CEP and HMG modelled “no deal” scenarios that assume the implementation of tariffs on goods trade and higher non-tariff barriers (NTBs) to both goods and services trade. The HMG study finds that no deal could mean that UK GDP per head is 8%-9% below baseline, with the range depending on future immigration policy. The HMG studies assumes that productivity growth is lower under no deal because the economy is less open to trade. Economic theory and empirical evidence tends to show that economies which are more open to trade, have higher rates of innovation and productivity. Therefore, an economy that displays higher barriers to international trade is likely to experience slower productivity growth. Similarly, the CEP study provides two estimates for no deal under different productivity assumptions. With no impact on productivity, GDP per head is projected to be 3.5% lower than the baseline in 2030, or 9% lower assuming a negative impact on productivity.

Meanwhile, NIESR modelled an “orderly no deal” scenario under which tariffs are re-imposed and NTBs rise, but with emergency arrangements put in place to avoid significant disruption to trade and travel. The “orderly no deal” scenario results in a smaller negative impact on the UK economy compared with most of the other no deal scenarios, with GDP per head projected to be 3.7% below the baseline.

Various “deals” would lessen the economic hit

The studies show that various forms of a “deal” with the EU could result in a less negative impact on the economy than a “no deal” scenario, with the scenarios most comparable to the government’s current negotiating position indicating that GDP per head could be 2%-3% below baseline in the long-run.

Short-term impact:

The political declaration

The Bank of England models two scenarios in the short term (to 2024) based on different economic partnerships under the withdrawal agreement and political declaration. The scenarios are labelled “close” and “less close”, incorporating different assumptions about the scale and scope of new barriers to trade. Both scenarios are consistent with the broad terms of the agreed objectives and principles of the economic partnership, i.e. the political declaration. The study indicates that GDP could be 1%-3% lower in 2024 relative to the trend just before the EU referendum.

Long-term impact:

The backstop

The NIESR and CEP/UK in a Changing Europe studies model the impact of the UK remaining in the backstop indefinitely, after the transition period ends, i.e. the UK remains in the customs union with no tariffs or quotas. The studies indicate that remaining in the customs union would result in a smaller loss to the UK economy than in other scenarios such as an FTA or no deal scenario. However, some services providers would lose market access in this scenario and consequently, the studies make some additional assumptions regarding the impact on services trade. In the NIESR paper, a reduction in services trade of 50% is assumed while CEP assume an increase in NTBs of 7.3%. The NIESR study suggests that GDP per head could be 1.9% below baseline by 2030 compared with 3.0% under FTA and -3.7% under no deal. CEP/UK in a Changing Europe reach a similar conclusion (1.9% below baseline, with no productivity assumption4), though the projected loss increases to 5.5% below baseline when accounting for productivity effects on growth.

Proposed deal and FTA

The NIESR paper also models a scenario assuming the withdrawal deal is followed by an FTA, with the assumption that goods trade frictions and NTBs are higher than those which Norway or Switzerland have with the EU, alongside a significant reduction in services trade (60%), based on the lower bound of empirical estimates ranging from 61-65% (Ebell 2016). This would cause a more negative impact on the UK economy than the deal and backstop scenario illustrated by NIESR due to higher frictions on goods and services trade, with GDP per head expected to be 3% below baseline.

The White Paper (Chequers)

The HMG analysis projects that the lowest economic impact would occur if the government achieved a deal with the EU modelled on its white paper (i.e. the Chequers agreement). This assumes a close customs arrangement with the EU and very low non-tariff barriers. The usefulness of this analysis is questionable, since much of it was undertaken well in advance of the agreement on the UK-EU political declaration, and the UK’s negotiating position has since shifted. The government’s proposed deal is not modelled, but an FTA would likely include a higher level of non-tariff barriers.

More plausibly, the HMG study includes a modified white paper scenario that assumes some increase in NTBs, such as checks at or behind the border and other regulatory costs. This is likely to be more comparable to a scenario consistent with the objectives of the political declaration and again implies that GDP per head could be 2%-3% below baseline by 2034. In a less ambitious, “average FTA” scenario, GDP per head is projected to be broadly 5% below baseline, reflecting even higher NTBs for goods and services.

Chemicals and motor vehicles see most negative trade impact

Sectoral analysis from the HMG study shows that manufactured goods trade would see the greatest hit in the event of a no deal, with additional trade costs on UK-EU trade estimated expected to be equivalent to 9%-17% of the value of trade compared with today’s arrangements. Chemicals, pharmaceuticals, rubber & plastics, and motor vehicles are particularly vulnerable to a no deal Brexit or an FTA, which could reduce GVA in each sector by 18-23% and 11-22% respectively (see Figure 3). This is due to the high non-tariff barriers in these sectors—notably customs procedures and regulations, such as rules of origin documentation, administrative costs and delays at the border. For most services sectors, a no deal scenario could result in a reduction of GVA of 5%-10%, relative to the baseline.

North East, North West & West Midlands are most exposed to “no deal”

“No deal” and the regions Regional analysis derived from the sectoral analysis in the HMG study notes that areas that trade more with the EU or are specialised in sectors that will face greater trade costs are likely to be the most impacted by Brexit. HMG used UK export profiles and economic production in each sector to estimate the regional impact. The modelling also takes into account integrated supply chains and the knock-on effects from the affected region. However, the analysis does not capture any changes to migration, but notes that under a scenario of zero net inflows of EEA workers, the regional impact would likely be greater.

In a no deal scenario, with motor vehicles and chemicals the most affected sectors, the study suggests that the North East would see the largest negative impact on economic activity. The smallest change to economic activity is estimated for London as it is relatively more specialised in services, particularly financial services, which are projected to be relatively less affected in a no deal scenario than manufacturing. In terms of the nations, the exposure of the manufactured goods sector to trade disruption translates to sizeable reductions in economic output in Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland.

White paper scenario

London and the South East are estimated to be the most affected regions in the two white paper scenarios, although the impact is small relative to other scenarios. These results reflect the two regions’ reliance on financial and business services and the relative increase in trade costs that would be experienced upon leaving the single market in services.

Long-term impact of Brexit on GDP per head, % difference from status quo baseline (Summary of scenarios published in November 2018)

Summary of trade only impacts on UK sectors, compared to today’s arrangements

Summary of trade policy impact on UK nations and English regions compared to today’s arrangements

Chris Buxton

CEO – British Fluid Power Association

December 2018